Late last year, US Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) ran a Twitter poll asking her followers to weigh in on a “national divorce between “Republican” and “Democratic” states (since her Twitter account has since been suspended, I’m relying on reportage from the New York Post to describe it). The non-scientific results: 43% favored said “national divorce,” 48% opposed it, 9% pronounced themselves undecided.

The “national divorce” talk has only increased since then, and of course there’s nothing new about the concept. As you may recall from high school history classes, hundreds of thousands died in a war over the last attempt at such a thing in the mid-19th century.

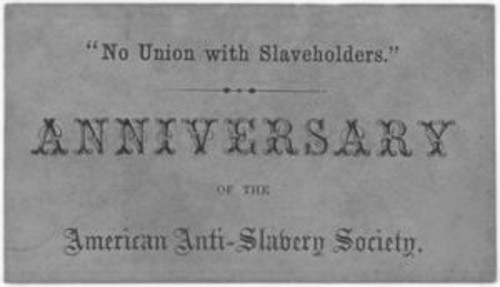

I’ve got nothing against secession as such. If people don’t want to remain affiliated with a polity, they should be free to exit the relationship. In fact, the namesake of the media center I write for, William Lloyd Garrison, encouraged NORTHERN secession: “No union with slaveholders!”

On the other hand, the notion of such a “divorce” at the level of the existing states raises some serious questions that most supporters don’t seem interested in addressing.

First and foremost, perceived connection to, or distaste for, a particular political party doesn’t seem like a good way of divvying up territory.

Different pollsters use different formulas to calculate the “partisan leans” of states, but let’s use the 2020 presidential election result as a proxy. Wyoming is the “reddest” state, won by Republican Donald Trump with 69.9% of the vote. Democrat Joe Biden’s best performance (excluding the District of Columbia, which isn’t a state, where he received 92.1%) was in Vermont, where he polled 66.6%.

So even in the “reddest” or “bluest” states, around 1/3 of voters (not to mention the total population) aren’t “red” or “blue.” Secession would maroon them in de facto one-party states, as opposed to offering them representation in national bodies where their preferred parties have a voice.

Even hand-waving all that away, there are other “nuts and bolts” issues to think about.

For example, what happens to Washington’s “national debt” when the states leave? Does it just get defaulted on? Or does it get split up … and if so, how? Pro rata by population? Weighted on the basis of whether the state was an overall “donor to” or “beneficiary of” federal largess?

How about military assets? Does New Mexico suddenly become the world’s second-largest nuclear power because so many US nuclear weapons happen to be stored at Kirtland Air Force Base, or does each state get a few warheads, along with a proportional distribution of aircraft, helicopters, tanks, etc.?

Oh, and we should probably discuss borders and travel. Will the former US operate like the Schengen Area’s 26 European countries which allow mutual travel without passports and border searches, or will a New York to Los Angeles flight with a layover in Denver turn into the customs nightmare equivalent of traveling from Moscow to Buenos Aires via Mozambique?

Divorces get messy even when they’re amicable. Would this one be worth it? Perhaps we should all consult our attorneys first.

Thomas L. Knapp (Twitter: @thomaslknapp) is director and senior news analyst at the William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism (thegarrisoncenter.org). He lives and works in north central Florida.

PUBLICATION/CITATION HISTORY