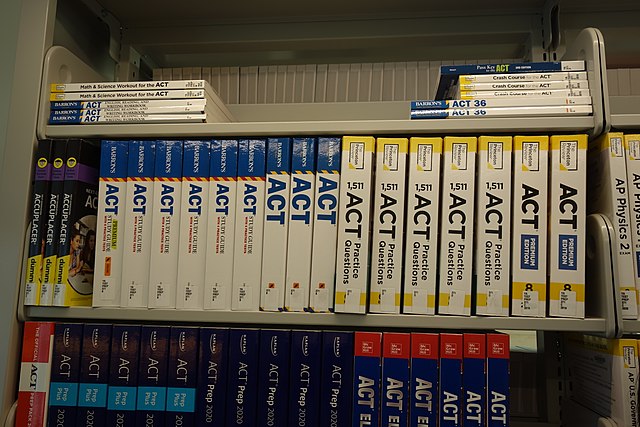

For this fall’s college freshmen, standardized tests weren’t as crucial in determining their selection as they would have been before 2020. Hundreds of educational institutions waived exam requirements when COVID prevented on-site administration. Some even excised the tests from the application process entirely. Yet Jeffrey Selingo reports that “something strange happened: Teenagers continued to sign up for the exams” (“The SAT and the ACT Will Probably Survive the Pandemic—Thanks to Students,” The Atlantic, September 16).

This devotion to getting an edge into colleges has remained persistent even a year after the Operation Varsity Blues investigation revealed how much of the admission criteria were being exaggerated or outright fabricated. With colleges replacing their on-campus offerings by remote video instruction — and online course materials like those long made accessible for free by initiatives like MIT’s OpenCourseWare — elite colleges have much less to offer in return for the tens of thousands in annual tuition they still charge. How has their draw remained so persistent?

Maybe it’s less that their wares are uniquely valuable than that they’ve closed off alternatives. Kevin Carey explains in The End of College that “the higher-education industry receives hundreds of billions of dollars every year in the form of direct appropriations, tax preferences, and subsidies for their customers in the form of government scholarships and guaranteed student loans. The only way to get that money is to be an accredited college. And the accreditation system is controlled by the existing colleges themselves, who set the standards for which organizations are eligible for public funds.”

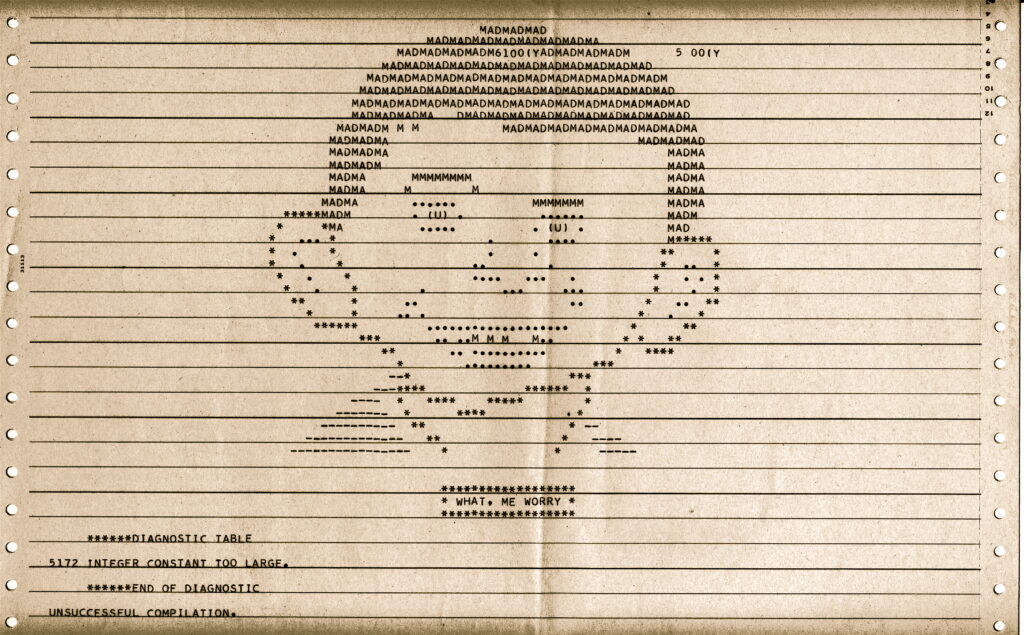

Standardized tests provide the accreditation monopoly with the data the top-down system needs to function. As anthropologist James C. Scott observes, “those at the greatest distance from ground zero of the classroom” particularly benefit from having “an index, however invalid, of comparative productivity and a powerful incentive system to impose their pedagogical plans.”

When Steven Levy’s Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution became one of the earliest journalistic accounts of the culture of computer programmers, Levy noted their insistence on evaluating each other by the quality of their programs, eschewing what they considered “bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race, or position.” In an addendum to a 2010 reissue of his book, Levy found many of its personalities had retained that spirit, as expressed by Bill Gates: “If you want to hire an engineer, look at the guy’s code. That’s all. If he hasn’t written a lot of code, don’t hire him.”

Higher learning — and its certification — can follow computer power’s path out of elite institutions to everyday ubiquity. If its participants can win the freedom to choose, share and exchange, the process can become more equitable as well as less bogus.

The Garrison Center’s Joel Schlosberg wrote his SAT essay on freedom in the science fiction of Eric Frank Russell.

PUBLICATION/CITATION HISTORY

- “Testing, Testing, One, Two, Zero” by Joel Schlosberg, The Citizen [Chicago, IL], September 11, 2020 (both web and print)

- “Testing, testing, one, two, zero” by Joel Schlosberg, The Lebanon, Indiana Reporter, September 24, 2020

- “Testing, Testing, One, Two, Zero,” by Joel Schlosberg, OpEdNews, September 25, 2020

- “Despite not needing to, college-bound students flock to ACTs, SATs,” by Joel Schlosberg, Greater Southwest News-Herald [Summit, IL], September 25, 2020

- “Testing, Testing, One, Two, Zero,” by Joel Schlosberg, Ventura County, California Citizens Journal, September 26, 2020