A celebrity who unleashed a frenzy of media attention with an unexpected attainment of a term in political office, despite being famed more for an outlandish personal style and uninhibited public statements than governmental experience, garnered insufficient ballots to win the 2020 US presidential election.

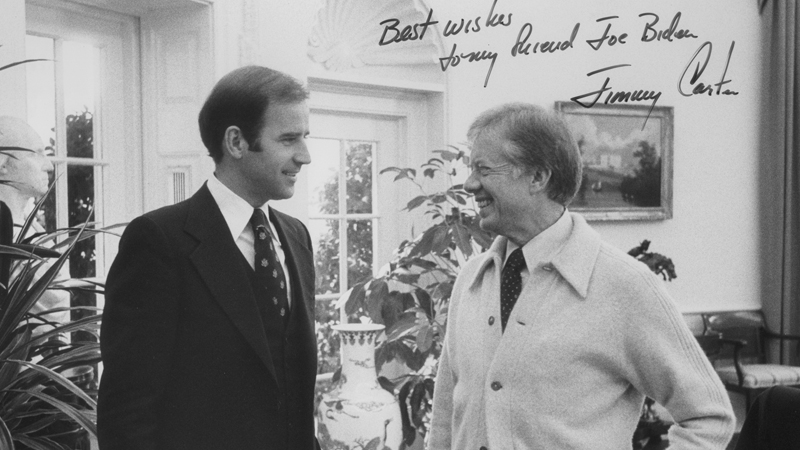

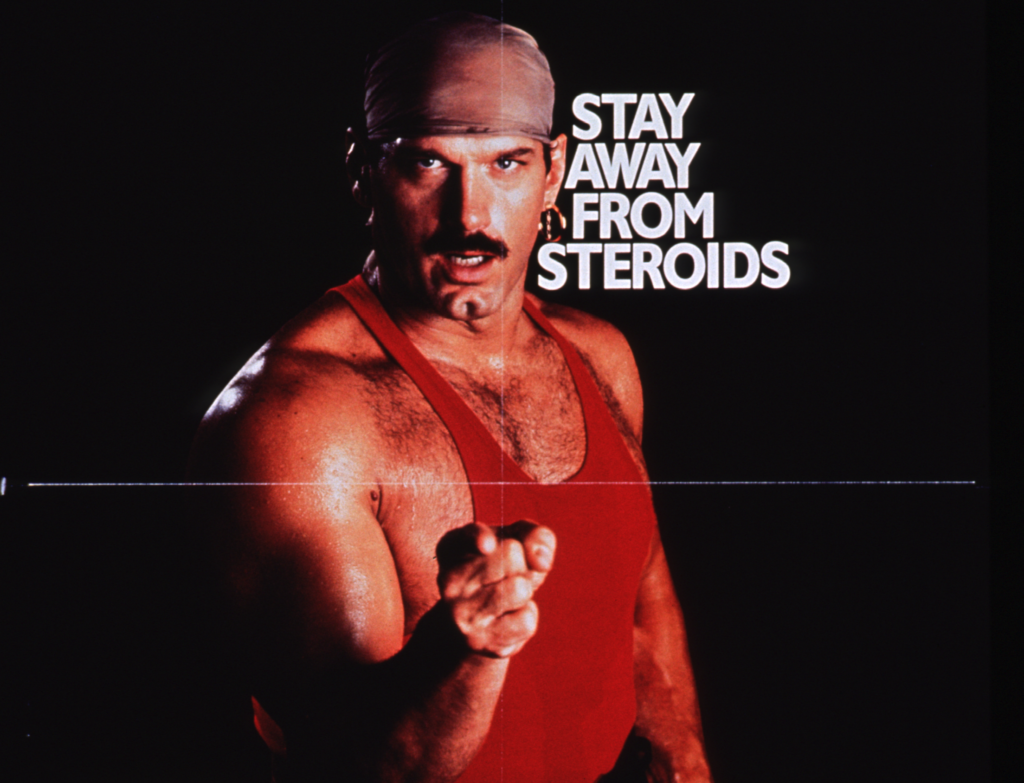

The slightly over 1,500 votes on the Green Party of Alaska line for former Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura may seem a mere footnote to the failed re-election bid of Donald Trump, whose level of support for Ventura’s rerun was much less than the “one hundred percent” promised at WrestleMania in 2004. Yet the success of referendum initiatives for drug decriminalization, two decades after Ventura’s endorsement of such measures was viewed as no less outrageous than his feathered boas, hints that he may have had more to offer than a coincidental foreshadowing of the paths from performance to politics of Trump or Ventura’s movie costar Arnold Schwarzenegger.

In his 1999 book I Ain’t Got Time to Bleed: Reworking the Body Politic from the Bottom Up, Ventura argued against drug prohibition not only on pragmatic grounds that it would be ineffective and counterproductive, but that “the government has no business telling us what we can and can’t use for pain relief and in matters of our own health.” Despite bragging to Reason magazine that year about how “I’ve taken the libertarian exam and scored perfect on it,” his record in office was less consistent, and he failed to sustain an alliance with libertarians.

However, Ventura was right to note that “we’ve gotten into the bad habit of looking to the government to solve every personal and social crisis that comes along” and that “there are a lot of good causes out there, but they can’t possibly all be served by government.”

Ventura’s proposed remedies, such as legislatures spending one year in four pruning old laws rather than passing new ones, may not have been the most practical ways to achieve that ideal. But such a healthy skepticism of the status quo could boost efforts to rebuild voluntary civil society and mutual aid. And despite his Green Party of Alaska nod being unsought, and at odds with the national party’s backing of longtime Green New Dealer Howie Hawkins, it should inspire the Greens to return to their own roots in proclaimed key values of grassroots democracy and decentralization.

In the 1987 movie The Running Man, Ventura portrayed “America’s own Captain Freedom” as a foe of Schwarzenegger’s freedom fighter. Its tagline predicted that 2019 would be a time when “America’s finest men don’t run for President.” Ironically, the finest ideas of the man who played Captain Freedom in the movies might help the USA of the 2020s escape from the ideological confines of previous decades.

New Yorker Joel Schlosberg is a contributing editor at The William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism.

PUBLICATION/CITATION HISTORY

- “OPINION: No Body for president? Pay Mind” by Joel Schlosberg, Richmond, North Carolina Observer, 11/10/20

- “No Body for President?” by Joel Schlosberg, Creston, Iowa News Advertiser, 11/11/20

- “No Body for President? Pay Mind” by Joel Schlosberg, CounterPunch, 11/12/20

- “No Body for President? Pay Mind.” by Joel Schlosberg, OpEdNews, 11/12/20

- “No Body for President? Pay Mind.” by Joel Schlosberg, Ventura County, California Citizens Journal, 11/21/20