New York City Council candidate Alexa Avilés asserts that “the free market will never provide decent housing for all, and we should stop pretending otherwise” (“The Free Market Will Never Provide Decent Housing for All,” The Indypendent, April 2). Who’s pretending?

Avilés doesn’t outright claim that the current housing market is free, but implies that a free market would reinforce the existing power of “banks and corporate landlords” over “tenants in private housing, NYCHA [New York City Housing Authority] residents, and small homeowners.”

In treating the latter as the only beneficiaries of intervention in the market — and conflating a free market with policies that “let big developers take control” — Avilés ignores what Roderick T. Long notes are the far larger effects of “regulations that strangle competition in the housing market.”

Assuming that “developers’ greed drives gentrification and displacement” obscures the ways that limiting competition distorts supply and demand. Market competition compelled stockbrokers, who are not generally distinguished by an absence of greed, to reduce trading fees from $199 to $8.

Long concludes that a free housing market would be one “with landlords competing for tenants,” so that “rental contracts would cease to be as one-sidedly favorable to the landlord as they often are today.” Tenants would also enjoy more power to take many of the steps recommended by Avilés toward ownership, such as “the opportunity to collectively purchase” their buildings.

Moreover, any free market approach must make unjustified land claims null and void. As Murray Rothbard put it, in such cases any “reform is picayune and fails to reach the heart of the question” short of “an immediate vacating of the title … with certainly no compensation to the aggressors who had wrongly seized control of the land.”

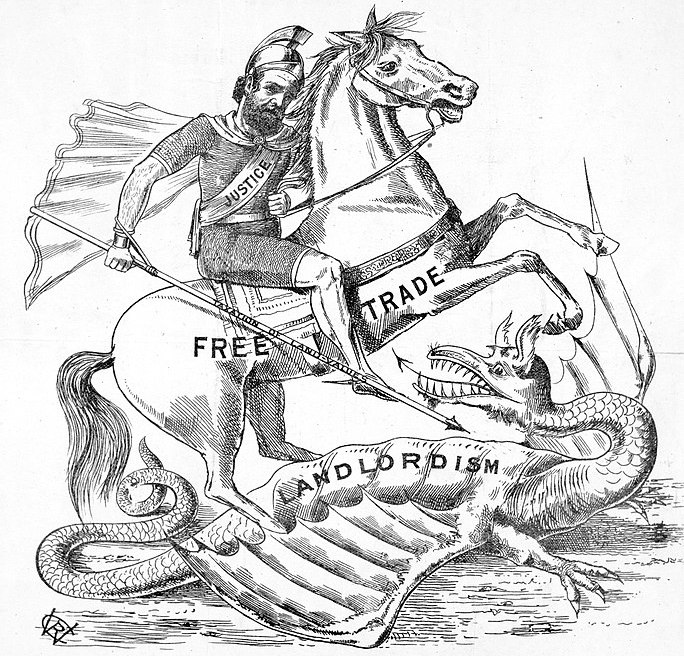

Avilés’s “Green New Deal for NYCHA” could take a page from Franklin Delano Roosevelt and revisit the writings of Henry George, who carried forth the tradition of combining free trade with land reform pioneered by such market liberals as Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and Herbert Spencer. FDR wanted George’s works to be “better known and more clearly understood” since they “contain much that would be helpful today.”

New Yorker Joel Schlosberg is a contributing editor at The William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism.

PUBLICATION/CITATION HISTORY

- “The Finest Trick of the Developer is to Persuade You That Free Markets Should Not Exist” by Joel Schlosberg, Anchorage, Alaska Press, 04/07/21

- “The Finest Trick of the Developer is to Persuade You That Free Markets Should Not Exist” by Joel Schlosberg, Ventura County, California Citizens Journal, 04/13/21