If you live in Arkansas, Mississippi, Montana, North Carolina, Texas, Virginia, or Utah, you can’t visit Pornhub — one of the most popular “adult content” sites on the Internet.

In response to state laws requiring “adult content” sites to verify the ages of its users and prevent minors from seeing videos of naked people doing you know what, Pornhub told its servers to simply refuse connections originating in those states.

That’s the fantasy.

Here’s the reality:

Getting around the restriction is so easy that most minors can figure out how to do it in a few minutes.

They don’t need to buy fake IDs, or steal their parents’ drivers’ licenses, or anything like that.

All those minors — and adults just not wanting to divulge their personal information — have to do is pick a free or cheap Virtual Private Network (VPN) service.

Voila! They’re no longer accessing the site from Arkansas, Mississippi, Montana, North Carolina, Texas, Virginia, or Utah, they’re accessing it from the Netherlands, Switzerland, or Japan.

So, why are these laws getting passed? There’s no way they’re going to “work” in the sense of stopping your 12-year-old from watching porn if he or she wants to watch porn.

These laws are just a form of government “virtue signaling” by politicians.

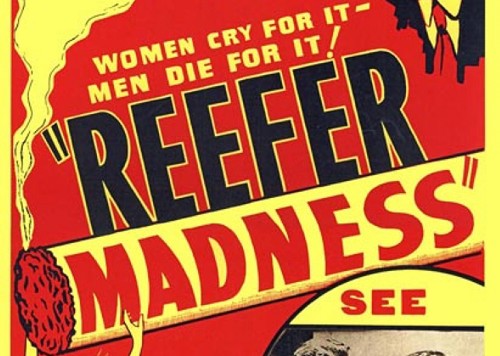

Those politicians induce moral panic among parents — “what if my 12-year-old sees porn? OMG!” — then cater to that moral panic with legislation that changes nothing but conveys a political message to those parents. The message is “I want to protect your children … vote for ME.”

If you’re a parent, I’m going to assume you’re not a lazy or careless parent.

If that’s the case you SHOULD be insulted by the claim that you’re not competent to effectively supervise your child’s Internet use, and you SHOULD tell those politicians to mind their own business and let you run your household as you see fit.

But for any issue, there’s a voter demographic that’s predisposed to fall for moral panic rhetoric and gratefully vote for any politician who makes them feel “safer” with silly and ineffectual legislation.

If you’re a voter (I won’t judge you if you aren’t), I urge you to resist the temptation to join any of those voter demographics.

With respect to this particular issue, supervising your children’s Internet use is your job, not the government’s. And you’re still going to have to do that job, because these laws can’t.

Thomas L. Knapp (Twitter: @thomaslknapp) is director and senior news analyst at the William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism (thegarrisoncenter.org). He lives and works in north central Florida.

PUBLICATION/CITATION HISTORY