Donald Trump’s attempts at “fostering unity and a deeper understanding of our shared past” have a chance to succeed — by spurring the very sort of “revisionist movement” he denounces in his March 27 executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.”

Not that Trump’s “solemn and uplifting public monuments” will engender much high-mindedness among the American public, even though they will surely avoid quoting from Fart Proudly: Writings of Benjamin Franklin You Never Read in School. And Trump’s trumpeting of America’s “unmatched record of advancing liberty, prosperity, and human flourishing” is at odds with his 2017 inaugural address describing a country in which heretofore “there was little to celebrate for struggling families all across our land,” since “for too long, a small group in our nation’s Capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost.”

But the administration’s very heavy-handedness might make Americans think twice about what they think they know about their history. On April 2, New York Times contributor David W. Blight insisted that what Trump dubs a “revisionist” approach is necessary to “maintain relevance,” and that “many Americans … actually prefer complexity to patriotic straitjackets.”

The newspaper wasn’t always so charitable to the revisionists. In 2007, Howard Zinn responded to Walter Kirn calling his A Young People’s History of the United States less devoted to “telling the truth” than “editing and motivating” in The New York Times Book Review with a letter to the editor insisting that “there is no such thing as a single ‘objective’ truth” independent of “the viewpoint of the historian.” This year, a contribution by Jeet Heer discerned “a proto-Trumpian politics” in Murray Rothbard viewing America’s rules as “a sham that ripped off ordinary citizens” (“Why We Got Kash Patel and a ‘Gangster Government’,” January 30).

Yet the Rothbard who Heer sees as yearning for rule by real-life equivalents of “the mobster antiheroes of the ‘Godfather’ movies” had no use for the not-so-little “Caesar in the White House” who imposed wage and price controls in his 1971 Times op-ed “The President’s Economic Betrayal,” or Nixonian Republicans who “have forgotten their free enterprise rhetoric and are willing to join in the patriotic hoopla.”

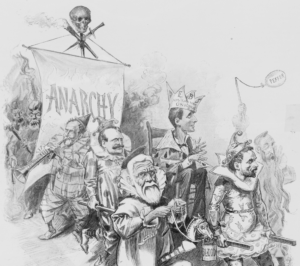

In contrast, the February 1976 issue of Rothbard’s The Libertarian Forum lauded “the Revisionist, even if he is not a libertarian personally” since “to penetrate the fog of lies and deception of the State and its Court Intellectuals” is “a vitally important libertarian service.”

New Yorker Joel Schlosberg is a senior news analyst at The William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism.

PUBLICATION/CITATION HISTORY

- “Trump Makes History Again? Great…” by Joel Schlosberg, CounterPunch, April 4, 2025