Some of the richest young heirs plan to use their inherited wealth “to undo systems that accumulate money for those at the top” despite being among them (“Silver-Spoon Socialists,” The New York Times, November 29). Convinced that “true wealth redistribution means redistributing authority” rather than mere largesse, they are “investing in or donating to credit unions, worker-owned businesses, community land trusts, and nonprofits” that spread power as well as money.

Such alternatives have long been dismissed as marginal, it having been assumed that only concentration of political power can effectively fight concentration of economic power. As Doug Henwood has advised anti-corporate protesters, “socialize Merck, don’t dissolve it,” since he considers “large, complex organization” necessary. Such urgings were little needed at the close of a twentieth century when socialization had become almost synonymous with nationalization (or at the very least heavy regulation).

Yet the move away from such a conflation two decades into the twenty-first century was anticipated as far back as the nineteenth, when the economic stratagems of Josiah Warren, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Benjamin Tucker aimed at what Tucker called “subjecting capital to the natural law of competition.” A freer market could “socialize its effects by making its use beneficial to all instead of a means of impoverishing the many to enrich the few.”

Even as the twentieth century produced unprecedented amassings of wealth and power, attentive historical scholars confirmed Tucker’s view that legal privileges entrenched dominant firms and blocked the benefits of market exchange in the realms of banking, real estate, international trade, and invention. Bertrand Russell observed that “the harm that is done by great industrialists is usually dependent upon their access to some source of monopoly power.” Gabriel Kolko showed how “it was not the existence of monopoly that caused the federal government to intervene in the economy, but the lack of it.”

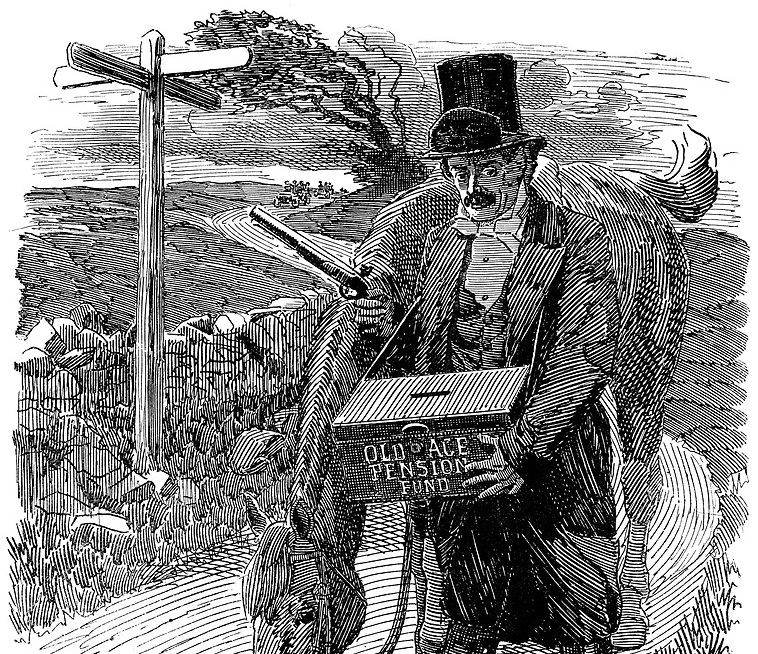

The sources of monopoly power identified by Tucker are still the primary factors that distort free trade into unfair trade. Those interested in using what they have to help have-nots should aim to reroute the economy beyond those barriers — or remove them entirely.

New Yorker Joel Schlosberg is a contributing editor at The William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism.

PUBLICATION/CITATION HISTORY

- “The negative philanthropic highway” by Joel Schlosberg, Lake Havasu City, AZ News, December 7, 2020

- “The negative philanthropic highway” by Joel Schlosberg, The Lebanon, Indiana Reporter, December 8, 2020